![]()

THEME I

THE ORIGINS OF WORKSHOPS IN AND AROUND ROUEN

(From 1840 to 1912)

Before beginning the story of the "Quatre-Mares" railway workshops, we will first retrace the history of the plants that preceded them in and around Rouen.

In 1840, the French railway industry, still in its infancy, was confronted with a major problem. If the construction of the carriages and wagons did not pose too many difficulties, the bodies of the vehicles resembling those of stoutly built stagecoaches, it was not of same for the locomotives. French builders were so few and far between that they were unable to deliver a large number of machines in a short time. The English companies, on the other hand, were much better placed. By 1840, they could already build 400 locomotives a year. Furthermore, their cost, including delivery, was between 10 and 25% cheaper than those built in continental Europe.

It was just at this time when the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de Rouen started to explore the market for potential suppliers. However, unlike other companies, rather than benefiting from the lower prices resulting from a temporary saturation of the English market, it decided to have its locomotives built locally but with the same financial and technical guarantees. Thus in July 1841, the board informed its shareholders that a company had offered to manufacture locomotives and tenders in Rouen itself. This was Messrs Allcard, Buddicom & Company, created specifically for the purpose.

The transfer of their business to Normandy appears very much to have been a way to escape the competition that existed in England. However, there was also a speculative aspect to the deal. The company looked forward to the establishment of better links between Paris and London and the prospect of an extension of the line towards Le Havre and Dieppe that could result in big orders for their products.

The Chartreux Workshop

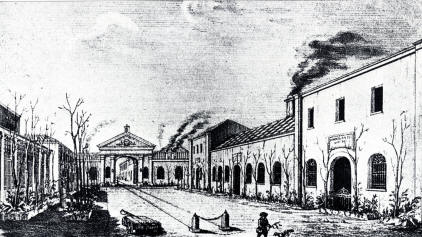

Allcard & Buddicom set up their first workshops - known as the Chartreux Works – within the walls of an old convent in Petit Quevilly in August 1841. Work was not lacking since the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de Rouen placed an order with them for the bulk of their rolling stock, that is to say 40 locomotives, 120 2nd class carriages and 200 wagons, thus providing employment for 500 workers.

The workshop of the "Chartreux" in Petit Quevilly

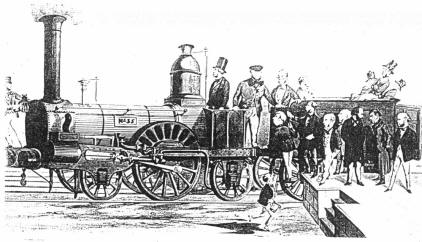

But this was not the sole activity of the workshops. Allcard & Buddicom’s contract also covered at an agreed fixed price, not only the building but also both the running costs and the maintenance of the material. The first carriages left the workshops in September 1842 followed by the first locomotives in October. These “BUDDICOM” locomotives were in fact a type of the “ALLAN CREWE” design, and manufactured under licence.

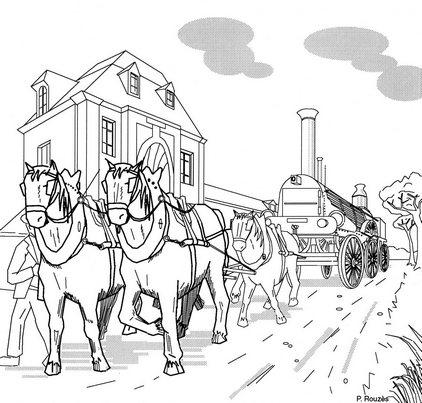

Transport of a locomotive by the road

The Chartreux-built rolling stock had to be hauled the several kilometres from the workshops to the station in Rouen on horse-drawn wagons so that was how the first locomotives and carriages were delivered to enter service in March 1843. The roads at that time left a lot to be desired and it is not difficult to imagine the problems with locomotives weighing up to 15 tons. Allcard & Buddicom were thus made keenly aware of the need to relocate their workshops closer to the railway.

The SOTTEVILLE – BUDDICOM workshops

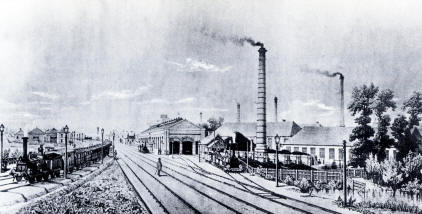

The transfer of the workshops to a site alongside the railway was carried out in December 1845. They were set up in Sotteville on the site of an old forge. Located two kilometres south of Rouen, they covered an area of 12.5 hectares of which more than four hectares were occupied by covered buildings.

the Buddicom workshops, 1890

At this time, Allcard & Buddicom had received an order from the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Rouen au Havre for its entire rolling stock, that is to say 32 locomotives, a total of 110 1st, 2nd and 3rd class carriages as well as 336 goods vans, trucks and other wagons.

The great number of outsiders who came to the region for the construction of the lines from Paris to Rouen and Le Havre were not to appreciated by everyone. Among the thousands were Belgians, Piedmonts, French and Irishmen. There were also English nationals in the key posts of the railway organisation who were particularly resented.

The events of 1848 were the excuse for anti-foreign demonstrations. British workers at Sotteville-lès-Rouen were maltreated, expelled even, to shouts of “Down with the English” or “Down with the railways”. Buddicom was obliged to intervene in person, deploying all his energy to preserve his undertaking from destruction.

This situation, however, was not unique to the Sotteville-lès-Rouen workshops or to the Rouen-Le Havre railway. The Compagnie du Nord and the Koechlin workshops in Mulhouse, for example, did not hesitate to recruit workers from the other side of the channel who were credited with greater technical skills.

In any case, there were many English at Sotteville-lès-Rouen. Allcard & Buddicom had in fact brought with them, the majority of their collaborators, the best known being John Whaley and his son George, who in turn were workshop manager until 1874 and 1885 respectively.

The new name of the company, “Buddicom & Cie”, appeared in 1854, well after the departure of Allcard who left the business in about 1847. This change in name was in fact linked to a modification of the agreement between the workshops and the Compagnie des Chemins de Fer de Rouen. The occasion arose due the application of the provisions adopted for the Rouen and Le Havre companies to that of Caen. From being just a contractor for the supply and maintenance of rolling stock, Buddicom became a associate of the consortium of lines which thus could control the workshops as a prelude to their absorption.

The railways of Rouen, Le Havre and Caen were not alone in this approach. Many companies, for reasons of convenience and cost, had so far seen fit to entrust their traction to independent contractors. However, now it occurred to them to relieve the pressure on their workshops by separating maintenance and construction. This was for two specific reasons: first, the significant increase in rolling stock that accompanied the multiplication and concentration of lines within coherent networks and second, the advent of a national railway industry capable of meeting the needs of all.

The merger of the Breton and Normandy lines in 1855 to create the Compagnie des chemins de fer de l'Ouest accelerated this tendency. In 1860, Buddicom handed over his workshops to the Ouest. After residing some time in Paris, he made his home at Penbedw Hall in the County of Flint in North Wales where he died on August 4th 1887. From then on, The Compagnie des chemins de fer de l’Ouest, limited the role of the workshops to the maintenance and repair of its rolling stock. It did not make any major changes to the workshops for nearly twenty years, in spite of the fact that its main line from Paris to Rouen ran through the plant and locomotive depot yards.

It was not until 1880 that the company decided to cure this problem within the framework of a programme of modernisation that also included the workshops of Rennes and Batignolles. In 1881, the main lines were re-laid on a new alignment with all the workshops on the left of the lines. This work involved the building of a new station for passengers and goods. It was also at this time that the company began the formalities leading to the annexation to the workshops of the old Sotteville-lès-Rouen cemetery. A wheel shop and a stores on three floors were built on this site in 1884-1885. This store contained everything required for the provisioning of the workshops themselves and for the locomotive running sheds in Normandy.

In July 1883, the new engine shed established at the junction of the lines from Rouen Rive Gauche to Paris and Le Havre to Paris was reputed to be one of the largest in Europe with provision for 108 locomotives and tenders. Its installation made it possible to establish on the site of the old depot, three workshops for heavy forging, boiler making and assembly. At the end of the century, the various workshops were organised around three poles: the locomotive and tender division, carriage and wagon division, and the manufacturing division. This latter, which included the forging mills, fitters shops, pattern making shops and foundries naturally supplied the first two divisions.

The purchase of the Compagnie de l’Ouest by the Chemins de fer de l’Etat (Réseau de l’Etat)

At the beginning of the 20th century, the financial performance of the Compagnie de l’Ouest was catastrophic and its management highly criticized. A law of July 13th 1908 authorised the Réseau de l’ Etat to absorb the Ouest and take over all its operations. As a result, six big companies, under state supervision, thus shared the French railway network. The Compagnie du Nord, The Chemins de fer de l’Etat, The Paris Orleans (PO), The Paris Lyon Méditerranée (PLM), The Compagnie de l’Est, and the Midi (later taken over by the PO), the last two the being healthiest.

For the Ouest railwaymen, this takeover by the Réseau de l’Etat brought better working conditions. Their wages now took into account the real cost of living and trade union rights were recognised. This made Sotteville a favourable ground for the development of the railway trade union movement during the years 1917-1920.

Why "Quatre-Mares"?

At the beginning of the 20th century, the public’s love affair with the railway was at its height. Developments in transport and technical improvements lead progressively to the transformation of the locomotives.

A programme to improve the workshops was submitted for approval by the Minister of Public Works on May 31st 1912. It highlighted the urgent need to increase the capacity of the repair workshops to accommodate ever more large modern locomotives. Indeed, following the commissioning of a growing number of such machines, the number of major repairs of État locomotives that for 1908 stood at 189, gradually increased to 237 by the year 1911.

Now on the Réseau de l’Etat, the Sotteville Buddicom workshops were the only ones capable of dealing with large locomotives. However, it could handle Pacific boilers only with the greatest difficulty. Furthermore, with the facilities and equipment then at its disposal, it could not cope with more than 85 major repairs per year. The fabrication and repair of locomotive parts for running sheds also required an increase in capacity. Urgent action was required.

However, it was not possible to envisage a simple transformation of the Buddicom workshop because of lack of the required space. Moreover, the site was needed for the expansion of the carriage and wagon shops that were by then also too small. Furthermore, it was essential neither to hinder operations, nor to increase its production temporarily until the day when another modern workshop could replace it. The management of the Chemins de fer de l’Etat was thus led to make provision for the construction of a new workshop in the vicinity of the Buddicom plant. On February 24th 1913, their project was submitted to the Minister for Public Works.

The project

To determine in detail the dimensions of and the equipment for the new buildings, the engineers, directed by Chief Engineer Bauer, based their ideas on the experience gained in the construction and the use of existing workshops both in France and abroad. These were notably the Epernay workshops of the Chemins de fer de l’Est of 1894, the Société Franco-Belge plant at Raismes built in 1908, the Société Cain works at Denain, the PO works at Tours, the ANF Blanc-Misseron plant at Crespin, all in France, and the Pennsylvania Railroad works in Altoona, USA.

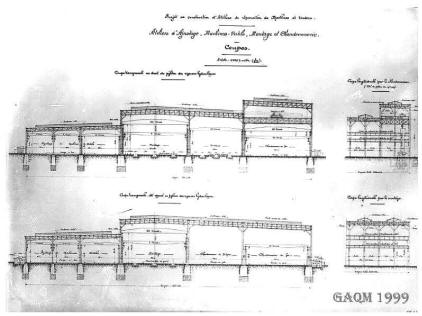

So in 1912, a plan of the layout of the new plant was drawn up. The boiler and machine tool shops, between which there would be a constant flow of both large and small parts, were to be on one level and in one building with a floor area 253m long by 105m wide of approximately 27,000 m2. This large building was to occupy more or less the centre of the site and be served by a network of railway tracks skirting the east and west facades and connecting to access and exit tracks at the north and south. The wheel shop and yard would be at the Le Havre end with the tube shop and annexes at the Paris end.

Project of construction in 1912

There was a good reason for this. The two groups of workshops would both require the handling of large numbers of loaded wagons because the bulk of their output would be for the running sheds. Thus, the coming and going of the wagons loaded with wheels on the one hand, and that of the wagons loaded with boiler tubes on the other would not be mixed up. In addition, the wagons that this traffic required would not mingle with those reserved for internal movements in the immediate neighbourhood of the principal building.

The forges would have to be located close to the fitters shop so that the delivery of iron and steel and spring leaves from the general stores would not be obstructed by the main building, wheel shop, and tube shop service roads.

The plant’s general stores would need to be placed near to the main building and in particular near to the fitters shop. The line serving it would have to be linked to the rest of the internal railway system by means of turntables. It would also be preferable that the store was located a little off the main internal system so that the waiting wagons for the traffic generated by the store would not interfere with the other movements of plant and materials within the works.

Other buildings such as the offices, paint shops, mechanical parts cleaning shops etc… would be conveniently located according to their specific function.

The total cost of the works in 1913 was estimated 16,485,000 Francs.

The choice of the site.

With the overall layout agreed, all that remained was to decide on the exact location of the workshops. The choice of site had to meet several criteria. It had to be relatively close to the old workshops in order to benefit from the presence, on the spot, as it were, of large numbers of workers (in fact there were 1500 railwaymen living in the commune of Sotteville lès Rouen alone).The construction of the future general stores close to the Buddicom workshops reinforced the idea of staying in the neighbourhood while at the same time finding a sufficiently large site that was easily accessible from the Rouen to Paris main line.

Two locations met these criteria. The first was grazing land beyond the rue d’Eauplet in Sotteville but which had the disadvantage of being below the level of the main line tracks. The alternative location was area called “Quatre Mares”, literally, “Four Ponds”. It was a boggy area, covered with old ballast pits, half in the Commune of Sotteville-lès-Rouen and half in St Etienne du Rouvray. It lay, like the first site, below the level of the main line.

However, this became the preferred choice of the engineers. Despite the very considerable amount of fill required, the site, measuring 850 metres long by 120 metres wide and bordered to the west by the Rouen to Elbeuf road and to the east by the Paris to Le Havre railway line, had the great advantage of already belonging to the railway company. Thus, there were neither the costs nor the delays of compulsory purchase and so it was possible to make a rapid start on the construction.

Because the site was partly in Sotteville and partly in St Etienne du Rouvray, the engineers decided to name the new workshops, “Les Ateliers de Quatre Mares”. However, in the minds of many people and for a long time afterwards, they were closely associated with the Buddicom works and so were referred to locally as “Les Ateliers de Sotteville”.

translation by John Salter

© GAQM2016 joel.lemaure@outlook.fr