![]()

THEME II

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE WORKSHOPS OF QUATRE-MARES

(from 1913 to 1919)

The foundations and earthworks

The French government gave the go-ahead for construction on April 16th 1913, and because of the urgency of the situation, already, by the following August, work was underway.

The first task was to clear and drain the site and to construct the concrete foundations for the buildings. Of a rectangular section and varying in depth from four to six metres, they were built to be flush with the finished ground level. The site was then backfilled to the top of these footings with 240,000 cubic metres of suitable material. This was well compacted to avoid any risk of settlement under the weight of the machine tools and the loads from the columns supporting the rails of the overhead travelling cranes.

Construction of the concrete foundations

During the excavation for the foundations, various objects dating from Gallo-Roman times were discovered, attesting to the long-standing human presence on the site. These artefacts are now on display in the Rouen Museum of Antiquities.

At the same time, the offices and the staff canteen, as well as a retaining wall skirting the present rue de Paris, at that time known as the Elbeuf to Rouen road or the Quatre-Mares main road, were built.

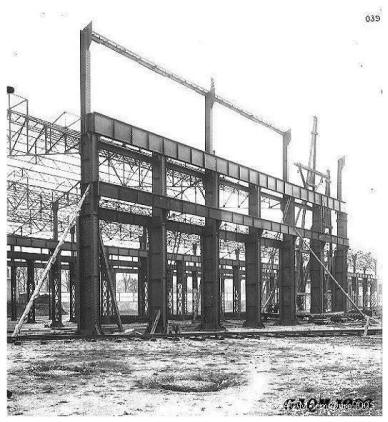

The metal structure

The erection of the metal structure was just as difficult as the earthworks. It was of entirely riveted construction with impressive dimensions for the beginning of the 20th century. Delivered pre-assembled to the site, the various sections were installed employing the methods of that time, namely hoisting masts, winches, guy-ropes, and props. The structure was going to have to be capable of taking loads resulting from the lifting of locomotives weighing around 100 tons as well as coping with simultaneous overhaul of considerable numbers of locomotives.

The erection of building C from the "Paris" side

The construction of the Quatre-Mares workshop is typical of the new industrial architecture of the beginning of the 20th century. It employed the most modern techniques and materials then available, including, for example, riveted steel lattice girders and reinforced concrete. It was in the forefront of industrial technology and innovation.

The British presence

With the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 and the consequent shortages of men and materials, work slowed down. However, the need for workshops for the construction and maintenance of railway locomotives was even more pressing after the enemy occupation of the industrial regions of northern and eastern France.

In 1915, with stalemate at the front, the Germans decided to take over the railway workshops in the occupied zone for the repair of their own rolling stock employed in the war effort. So railway plants in Lièges, Namur, Antwerp and Brussels in Belgium and Lille in France were all pressed into service by the enemy who could also rely on three of their own important works in the Cologne area, Cologne-Nippes, Oppum and Julïch.

In contrast, the lack of substantial workshops made it impossible for the British Army, which had come to France with its own railway material, to satisfactorily maintain the locomotives. The Corps of Royal Engineers therefore called for a repair workshop to be put at its disposal in France. As Rouen was the bridgehead for the arriving British troops, their choice fell on the Quatre-Mares plant, in spite of its unfinished state. In January 1917, an agreement was drawn up with the Chemins de Fer de l' État. Under its terms, the workshops would be taken over by the British Army which would complete the buildings and install the overhead travelling cranes. Track, machine tools, materials and accessories, lighting and power facilities would also be supplied and installed by British.

Building "B"

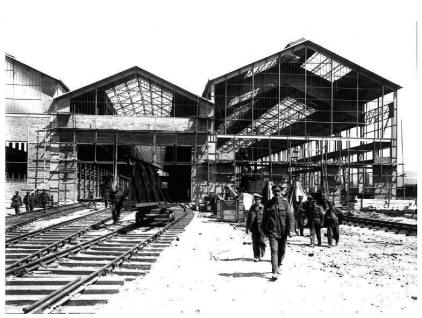

A detachment made up officers and men under the command of Lt.-Col. Cole RE quickly took over Quatre-Mares which became known as “Camp Locos’ Works”. Site operations started towards the end of February 1917. At that time, the assembly shop, the store, the boiler shop and the fitter's shops, the construction of which had been started by the company Établissements “Haour Frères” of Argenteuil, were just two unfinished skeletons more than 100 metres in length. As for the forge shop, only the foundations were visible. Very rapidly, teams were set up to create units designated as Railway Workshop Companies by the military authorities. Working with the British troops were qualified French personnel who were thus exempted from military service.

Paris-side gable ends of buildings A, B and C

Work began in the shops while the buildings were still under construction. Qualified fitters, turners, blacksmiths and boilermakers, draughtsmen and moulders mixed and poured concrete or erected columns, roof trusses and joists. In April, machine tools started arriving from England, followed closely by steam locomotive parts from Canada and the United States. However, their assembly had to start at once in workshops still in construction and without an operational overhead travelling crane.

First results

In July 1917, the first two locomotives were completed and entered service. The workshops were beginning to prove their worth. However the management had to demonstrate their ingenuity when confronted with a lack of some equipment.

Two Bellis and Morcom 400 kW DC steam-driven generator sets supplied by Babcock and Wilcox boilers were ordered in March. They began providing electric power to the workshops in October of the same year. Up to then, some machine tools had to be started by means of small temporary internal combustion engines.

Babcock boiler coal hopper and chain grate stoker

In August, a small makeshift pattern shop and foundry was set up in a contractor’s yard south of the main workshop. The building was a crude shed without proper ventilation. Power came from an old portable motor, bought at its scrap price and patched up to work for just a bit longer and it was a Ford motorcar which one day powered the blower. With lots of improvising, replacement spare parts were produced on an as-needed basis before complete repairs were undertaken. These were delayed for some time because of the lack of overhead travelling cranes. Among those, only three of a capacity of 8 tons in the erecting shop, and two of 10 tons in the boilermakers’ shop, were working in October. It wasn’t until February 1918 that the two 60 ton cranes were in service in the assembly shop.

Already by September 1917, however, the installation of equipment was well enough advanced for the reception of the first locomotives for repair and, in October, night shifts were introduced in the erecting shop. Boilers of about 140 horsepower were ready to provide the compressed air for the pneumatic hammers. That same year, 2.300 tons of concrete for the foundation were poured and 553 cubic metres of ballast were laid on the ground and for the tracks. Overall, 21,800 tons of material were brought into QM, including 3,962 tons of locomotive parts for final assembly. For the electric power requirements of machine tools and the overhead cranes, stationary engines with a total output of 473 hp were installed and connected up to generators. However, in the fitter's shop as well as in the wheel shop, except for the heavy duty machines such as the wheel turning lathes and vertical lathes for the steel tyres, which had their own electric motors, the machine tools requiring less power were grouped together and driven by line shafts and belts.

Building D

As of September 30th, a total of 34 locomotives had been assembled, tested, and put into service.

In October, the main buildings had been completed. The construction of barracks and the laying on of water supplies for the Workshop Companies was carried out in parallel to the construction of the workshops, their fitting out and the assembly of the locomotives.

Erecting the first locomotives

By the end of 1917, not only had the workshops been built, but 135 new locomotives assembled and five others repaired and put into service. The wheel shop had assembled 74 wheelsets, the smithy had produced 72 tons of forgings and the foundries 23 tons of copper and 225 tons of cast iron. By December 31st, more than 11,000 tons of locomotive parts had been handled in the yard. From no workers at all in February, the workforce gradually rose to 1000 by the end of October and, during November and December, on average, 1200 sappers and 300 German prisoners of war were assigned to the plant.

A new layout for the works

New Year 1918 was enthusiastically rung in by the night shift with a two-minute long peal on the bells of American engines, celebrating the prospect of reaping the rewards for all the hard work of the preceding months.

The installation of the overhead travelling cranes was nearly completed and the pattern shop, the foundries, the forge, and the machine and boiler shops had come on stream. Between January 1st and May 9th, 1918, more than 97 engines were assembled, before this work was halted, the workshops having to concentrate on repairs and the manufacture of replacement parts. In addition, the last German offensive of the war, in April 1918, forced the relocation of Chemins de Fer du Nord personnel and equipment to Quatre-Mares. This necessitated the wholesale relocation of the erecting shop, boiler shop and forge. In spite of the fact that it figured on the original plans, the forge shop was not yet built so the forges were installed in a purpose made temporary shed built on the site of the present wheel shop. It comprised two boilers, four steam hammers, two pneumatic hammers, metal shearing machines, bar cutting and bending machines, a total of 42 spring forging mills, the materials for steeping and annealing the springs, the large furnaces and other installations, together with the pipes and fittings necessary for the compressed air, steam, and hydraulic lines.

Chemin de Fer du Nord machinists

The transfer of the erecting shop to the former boiler shop required the excavation of new inspection pits. This operation began on May 15th concurrently with the relocation of the boiler making plant and the forging machines onto their respective new sites. One month later, although the concrete of the new pits was still “green”, they were already in use and the former erecting shop was placed at the disposal of the Chemin de Fer du Nord. In less than four weeks, more than 800 trucks of machine tools and supplies were evacuated from their Longueau and Asnières workshops to Quatre-Mares However, in addition to locomotive building and general repairs to machines, the expansion of the various departments made it possible to be of greater assistance to the running sheds with a significant production of new spare parts and repaired components. Production would continue for a few months after the Armistice.

The handover to the Réseau de l'État

It was not until the end of 1919, after the departure of the allied troops, that the Réseau de l'État took over the workshops and transferred its own machine tools and personnel from the locomotive section of the Sotteville Buddicom workshops. The acquisition by the Réseau of the equipment installed by the British greatly facilitated the resumption of activities in the new workshops without interruption to the repair of the locomotives.

Shield presented to the workshops by the "Royal Engineers"

on the occasion of their departure at the end of 1919Over the years from 1919 to 1938, this basic equipment was supplemented by the acquisition of many new machine tools.

translation by John Salter

© GAQM2016 joel.lemaure@outlook.fr