![]()

THEME V

THE WAR PERIOD

(from 1939 to 1944)

1939-1940: The troubled years

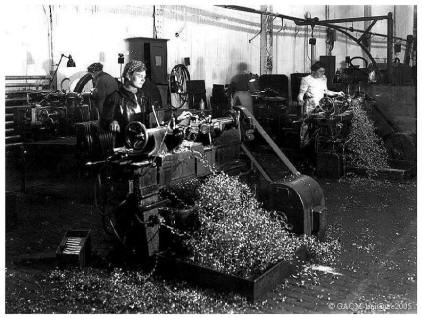

Like all Frenchmen and women, the people of Sotteville and St-Etienne-du-Rouvray didn’t believe that there would be a real outbreak of hostilities, not until, that is, the German invasion and subsequent occupation of their towns on 13th June 1940 plunged them into the horrors of the Second World War. The railways, for their part, were faced with a serious staff shortage. At Quatre-Mares, from a workforce of 1600, 400 were called up for military service. They were replaced by means of a massive recruitment of women, male auxiliaries and, thanks to an intensive training programme, by former unskilled workers and labourers.

Participation in the war effort

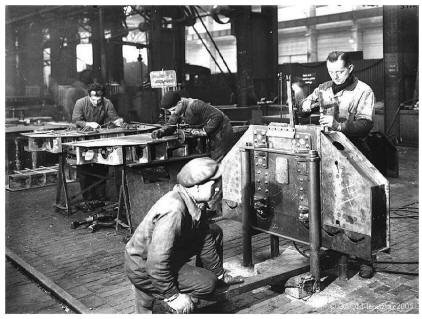

From 1939 and with the deteriorating international situation, QM’s wide ranging engineering capabilities enabled the workshops to turn their hand to the manufacture of armaments.

Production lines were commissioned to provide for France’s defence needs. Specializing in the machining of 37mm and 81mm projectiles, they could turn out 750 of the first and 1200 of the second every day. In the face of the staff shortage, the work was carried out by a team of 30 including 22 women. At the same time, QM was planning the production of 90mm anti-aircraft guns and had developed the entire method of assembly and manufacture of components, all of which would have been fabricated in the works, with the exception of the gun barrel to be supplied already machined by the Schneider Company of Le Havre.

The production line capable of turning out one gun a day was ready at the end of April 1940. Very soon however, events were to make it impossible to benefit from all the preparatory work because on May 9th 1940, the war had moved on and German Stukas were over Sotteville. The inhabitants were alarmed by one particularly long air raid warning but there would be 54 more in just the month of May. On the morning of Thursday June 13th, German troops entered the town. Sotteville, presenting a scene of utter desolation, had been abandoned by practically its entire population 5 days previously.

The railway allotments

Supply difficulties, as well as a particularly acute shortage of vegetables locally, made it necessary to increase the number of allotments, among which were those belonging to the railway. Amounting to 60 hectares of good land, they were placed at the disposal of nearly 5,000 Sotteville railway families.

These allotments, placed under the care of l’Association du “Jardin du Cheminot” in 1942, were situated on a wide alluvial meadow, subject to flooding in winter by the swollen waters of the Seine. It was ideal land for market gardening.

In 1939, the allotments represented 124,000m2. By 1941, they had grown to 277,000m2 and by 1942 to 473,000m2, comprising 2,264 individual plots of land, among which 50 were tended daily by the pupils of the training school and 40 were in the care of the 10 to 14-year-olds.

The main group of 2,036 plots extended over a distance of 4 kilometres. They were accessed by the Quatre-Mares bridge and the three main paths leading from it.

The administration of the allotments was provided by the Sotteville District Managers’ department which maintained an index file containing 4,000 cards for registering all the plot allocations and transfers.

L’Association du “Jardin du Cheminot” played an educational role for the allotment holders, supervising the 1,600 Sotteville members. One delegate per workshop or department acted as an intermediary between the office and the allotment holders. The association was also responsible for the distribution of tools and plants to the tenants. In 1941, the association gave out 610 garden tools and installed three pumps to provide water to those plots where it was in particularly short supply.

The Arrondissement of Quatre-Mares.

On 1st January 1941, QM became an Arrondissement. This gave it a national dimension and explains the uniqueness of its code number, 33920, like the eight other Arrondissements.

The occupation.

There were fewer occupying troops in Sotteville-lès-Rouen and Saint Etienne-du-Rouvray than in Rouen.

The German presence was primarily made up of civilians and Reichsbahn railwaymen: engineers, engine drivers and firemen, chief mechanics, senior foremen, and shed foremen, all conscripted to work on the occupied railway. Billeted on Sotteville inhabitants, their general HQ was in the Château Belliard.

In fact the occupation of Sotteville was all too real for the railway which from June 22nd 1940 was subject to the conditions of the armistice. Consequently, all the installations, including tools and stores as well as communication facilities were handed over intact to the German authorities. Specialised staff and rolling stock were placed at the disposal of the occupying forces.

At Quatre-Mares, the French engineer, M. Jandin, was obliged to have a working relationship with his German counterparts. About ten supervisors, in Reichsbahn uniform, were present at the workshops during the completion of work on the locomotives.

With the resumption of traffic on the Ouest region at the end of July 1940, the Germans began to be interested in the equipment and Sotteville MPD was designated as a holding centre for machines destined for Germany. At Quatre-Mares, more than 42 requisitioned locomotives were overhauled.

For the occupying forces, the railway at Sotteville was of the greatest importance. It was a hub for traffic between the north, east and west which made its installations, and even more so the labour force, invaluable. It was for that reason that from July 1940, ex-SNCF prisoners of war were repatriated from internment in Germany. Every week, they had to report to the German headquarters in Rouen to show their demobilised soldier's papers as proof of their continued presence.

1941-1942: The resistance gets organised

From the outset, railwaymen took an active part in the “Bataille du Rail”. They were a traditionally exclusive and close knit body of men who sought to stand up to the occupying authority’s representatives who they came into contact with every day. It was both this individual resistance and that of the organized networks which contributed to the final rout of the enemy.

A) The “low key”resistance

Aimed at hindering all activity and transport in the service of the enemy, this resistance was based on the slowing down of production or on deliberately engineered “accidents” and it was the former method which was particularly employed at the QM and Buddicom workshops.

The fixed character of these workshops’ equipment limited large-scale action against machines and particularly the use of explosives. In the Quatre-Mares erecting shop, the workers arranged for everyone involved to be present at the same time on one locomotive, and to wait in turn to add their specific component.

Because every worker had to fit it under the eyes of a German who was on the look out for any possible sabotage, while all this was going on, not much work was done!

It was true, anyway, the overseers didn’t really do much about it; they were there to see that the parts were fitted correctly and the production rate and such things didn’t bother them a great deal.

To the delays caused by the shop floor workers were those due to red tape and deliberately mislaid documents. At all levels, from the foreman to the person in charge of accounts, more time was taken than actually required for the job. It was these “accidents” and “human errors” that, repeated every day, amounted to genuine guerrilla action. It was sabotage without either explosives or explosions. For example, someone forgot to grease the parts of a locomotive so they wore out prematurely; defective parts were not always replaced so they broke down sooner or later and often in the middle of the countryside.

In addition to the above, there were other methods which were more difficult to pass off as “accidental” such as sand in the journal boxes which seriously damaged the axles, cut air hoses, chisels and other metallic objects in cylinders etc...

But the “low key” resistance was not aimed exclusively at hindering output. Workers also circulated anti-German pamphlets. Paper being in short supply, often it was just one single pamphlet for the entire plant. Passed quickly from hand to hand, it rivalled the numerous tracts distributed by organized resistance networks which were systematically hunted down by the occupying authorities.

On March 20th and 29th 1942, in spite of the checks carried out by the German supervisors, leaflets were discovered aboard locomotives delivered to the Reichsbahn after overhaul at QM.

Other expressions of resistance occurred very early on; they took the form of demonstrations and attempts to ferment strikes. For example, at 11 pm on June 22nd 1941, the day Germany invaded the USSR, a group of railway employees, singing “The Internationale”, set off from the place Voltaire for the station. All along the route, people were at their windows to show their support. Once at the station, the group scattered before the German authorities were alerted.

More surreptitious but no less symbolic was the clandestine laying of flowers on war memorials to mark November 11th. On the occasion of the publication of lists of men conscripted for work in Germany, the railway workers organised go-slows. However, full-blown stoppages were a different matter and so few were attempted, at least before 1944.

On the other hand, on the announcement of the death of a fellow countryman or an Allied victory, the workers demonstrated their support them by clocking on noisily, banging on their machines and by so doing, trying to start work as late as possible. But this type of industrial action strike rarely exceeded a few minutes with certain supervisors threatening to designate those responsible at random.

This regular, often daily, “low key” resistance helped to undermine the German organization but it was always dangerous for those who dared to take part. Workers held responsible for “accidents”, whether guilty or not, were subject to disciplinary sanctions while an “autonomous” saboteur, though not caught red-handed but suspected for a long time of resistance activities, often paid for actions committed by the organised networks.

B) The organised networks

The young communists at Quatre-Mares mobilised rapidly, linking up with the Franc-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP) of the Rouen region; the Bataillons de la Jeunesse and young Bretons seconded to the workshops also quickly lent their support to this group.

But they ran very serious risks. In fact the repression of communists had begun in 1939 under the Daladier government but it was dramatically intensified following the German invasion of the USSR on June 22nd 1941. In August of that year, the Germans published an official notice proscribing all relations whatsoever with the Communist Party or its members.

The Organisation Civile et Militaire (OCM) appeared in Normandy in 1942. It had its origins in the Armée des Volontaires and was politically more or less on the right. A good many of its members were executives or staff in Quatre-Mares workshops, unlike the FTP whose supporters came from Quatre-Mares but also Buddicom and Sotteville MPD. Their choice of action was also different. Whereas the FTP was characterised by its terrorist activity, the OCM specialized more on intelligence, infiltration, parachute drops, and arms caches in liaison with the Forces Françaises Libres (The Free French).

Resistance fighters were mercilessly hunted down by the Gestapo, one of whose techniques was to arrange for the employee to be called to the works office. This gave the suspect little chance of escape. Arrested and then tortured, some were shot at once while others were sent to concentration camps from which few returned.

The OCM has achieved celebrity though its "triangular" cell structure at Quatre-Mares. No action group, each which consisted of no more than three members, ever came into direct contact with other cells and only M Joubeaux of QM’s administrative department was in contact with the departmental members of the OCM.

The were many significant operations undertaken against the occupying forces by these Sotteville members of the Resistance, whether in the field of train derailment, sabotage, detention of weapons or terrorist attacks.

C) The armed resistance and its terrible consequences

From October 19th, young QM members of the FTP in conjunction with the Bataillons de la Jeunesse were responsible for a successful derailment between Malaunay and Pavilly on the Paris – Le Havre line.

The idea was to oblige the enemy, then launching an attack on Moscow, to maintain a significant army of occupation in France and thus help the Red Army which was bearing the brunt of Hitler’s attacks.” (Maurice Chouri, “Railwaymen in the bataille du rail”).

The operation was a real success for the FTP, but the German authorities were not slow to react. In reprisal, on October 22nd 1941, the Gestapo carried out a series of arrests in Sotteville targeting trade unionists and communists who for a long time had been suspected of activities against the occupying forces. After interrogation by the Gestapo in Rouen, the hostages were deported to Auschwitz, Sachenshausen, or Buchenwald. They all perished.

The attacks were often carried out with equipment and materials made by the railwaymen themselves. For example, Messrs Chenier, Lefevre and Menez, and their team of young Breton communists from the QM workshops, made spanners for removing rail sleeper screws, bomb casings which when filled with “cheddite”, an explosive made of potassium or sodium chlorate and dinitrotoluene, were used to blow up the air compressors at Quatre-Mares, immobilising the workshops for quite some time. In May and in September respectively of 1942, these kinds of explosives demolished the generators at the engine shed and the QM oxygen and acetylene plants

The Gestapo tracked down and shot members of the Resistance in order to weaken the networks. For example, on August 28th 1942, R. Cloarec and J. Bécheray were executed at Le Madrillet firing range for the possession of weapons. Employed at QM, they were both members of the Libération-Nord resistance group and were also suspected of liaising with active service units for the reception of parachuted weapons. On September 18th 1942, the QM young Bretons lost R. Chenier, one of their comrades from Rennes who was shot for the murder of a German officer on April 24th 1942.

But all these sacrifices were not vain, because each martyr of the Nazi oppression, the Jewish and political deportees and those executed, contributed to the awakening of consciences and a stirring of the masses who had for so long remained silent. Thus at the end of 1943, group actions manifested themselves, especially after November 11th when the ceremonies in memory of the dead of the Great War came to be identified with a sentiment of resistance.

QM broke with the traditional clandestine laying of flowers when on the night of November 10th 1943, a railwayman hoisted the French tricolour to the top of a chimney 40 metres above the ground.

At 10 am, the staff gathered in the front of the flag and sang the “Marseillaise”. The German officers give the order to remove the emblem but the shop foreman intervened and managed to negotiate for the flag to be taken down after a minute’s silence at 11 am. In February 1944, a strike took place supported by the whole QM workforce that lasted for 45 minutes. It came when the workshop administration and German overseers were discussing the timetable of the railwaymen’s shuttle train between Sotteville and Oissel, which were to be brought forward or put back fifteen minutes. The men chanted “bread and a pay rise” but all of them were at their posts before the return of the persons in charge of the workshops who had been informed by the supervisors.

On August 10th, employees at Sotteville station and in the workshops unhesitatingly supported the general strike called by the railwaymen’s section of the CGT (Confédération Générale du Travail). On the 13th, all activity ceased from Paris Saint-Lazare to Versailles as well as in Sotteville and throughout the entire Ouest region. This strike, systematically immobilising the main railway routes, would be invaluable to the Resistance, more than ever present at this moment of the German rout.

List of "shot or victims of deportation" reproduced on the war memorials of Sotteville-lès-Rouen SNCF establishments.

1 – From the Quatre-Mares workshops

R.Bécheray

R.Brault

M.Leblais

A.Bérault

R.Cloarec

G.Marti

E.Billoquet

P.Comte

A.Néphise

R.Blantron

A.Duval

M.Pautremat

M.Bouchard

B.Flamant

J.Roulland

E.Bouteiller

R.Gasnier

M.Voranget

F.Pelletan

M.Guilleux

M.Vallée

2 – From the Buddicom workshops

D.Baudouin

L.Jeantet

C.Pinson

A.Poirier

A.Bruneau

G.Lemaire

A.Ennebault

C.Monfray

3- From Sotteville-lès-Rouen Motive Power Depot

A.Bouget

R.Coutey

M.Malmaison

H.Boucaut

J.Douence

P.Oursel

Brunel

A.Forfait

A.Pichard

Blondel

G.Fouache

A.Robin

H.Breton

M.Genvrin

E.Texier

A.Boucher

A.Grillon

Vasse

R.Canton

R.LeroyThe training school

To shield the apprentices from the dangers of the air raids and to ensure that they had sufficient food at a time when rationing was severely affecting town-dwellers, in October 1942, the training school was relocated to a camp near Mesnil-sous-Jumièges, a small village downstream of Rouen and about 40 km from the workshops. Away from any threat from the skies, QM’s youngsters settled into their new surroundings.

In a cheerful atmosphere, 120 boys from 13 to 16 years old were housed in eight hastily built wooden barracks not far from the manor house of Anne Sorel, the favourite of King Charles VII. They lacked for practically nothing: a considerable amount of fitter’s and boilermaker’s equipment was sent to the peaceful village. There was even a football field and a basketball court, as well as a school hall.

The days passed peacefully between the flag raising ceremony early in the morning, the lessons and the sports activities. It should be mentioned some of the staff in charge refused to wear uniform which for the locals could have looked too much like that of the Petain-inspired youth movements or other political organisations of that period.

For the apprentices, being sent off to the country was far from destabilizing, quite the reverse in fact. Obliged to adapt to meet the needs of their life together, everybody rallied round. The main thing was to get accepted by the local farmers and to stock up with provisions.

Very quickly and until the return of the training school to Sotteville in 1948, the young people perfected but at the same time made use of their technical skills by trading their know-how for foodstuffs.

The traditional apprentice establishment gradually turned into a school were they learned about motivation and the solidarity: the apprentices repaired farm machinery, made ploughshares, alcohol stills, and even horseshoes, in exchange for butter, eggs and fresh meat (the school kitchen quickly became a veritable abattoir). Showing great ingenuity and resourcefulness and with the materials at hand, a theatre group put on plays, the tickets for which were paid for in kind. The school doctor also took on patients from the neighbourhood.

But everyone remained aware of realities of the war: on April 19th 1944, the apprentices could make out from Mesnil-sous-Jumièges, the red glow in the sky of the fires lit by the bombing of Sotteville. Moreover, many of apprentices put themselves in danger by supporting the local Resistance. For example, they hid large chunks of meat under the rear seats of the van which provided the transport between Mesnil and Sotteville.

The trips were made regularly, without hindrance, thanks to an agreement between the resistance and the local gendarmerie to allow the van to pass without any close inspection. On arrival in Sotteville, the meat was delivered to the Buddicom works canteen.

The Solidarity, The "C.N.S.C"

The aid for victims of the war in Sotteville came for the most part from two country-wide organisations: the Secours National Français (French National Aid) and especially from the Comité National de Solidarité des Cheminots (National Railwaymen’s Solidarity Committee) whose local Quatre-Mares Committee made the following appeal during its week of solidarity from 20 till 28 February 1943:

“On the occasion of this Week of Solidarity which has just begun, the Comité National de Solidarité des Cheminots of Sotteville Quatre-Mares considers it necessary, with so many of our loved ones subject to such distress, to address you personally, to your hearts and feelings, to explain the function of the Solidarity Committee.

The Solidarity Committee was created at the beginning of the war on the initiative of practically all the organizations representing railway employees, members of friendly societies, teachers, servicemen, artistes, and sportsmen who resolved to join together as one to help the victims of the conflict...

Those in distress are numerous in our ranks. The catastrophes and bereavements of which we are informed every day have naturally lead the Comité National de Solidarité des Cheminots to adopt a strict line of conduct: stand together, everything by the railwaymen, for the railwaymen.

Our mutual aid organisation, from its inception in September 1940, has never had the time to accumulate significant cash reserves. (...)

So today, again, we call on your humanitarian feelings to help us in our work and to rediscover the wonderful spirit of fraternity that we experienced after the tragic bombing of the motive power depot.

Do not forget that 15 million francs have already been distributed:

- To those made homeless,

- To the widows and the orphans of our dead,

- To our prisoners of war.

(...) We ask you to be as generous as you can and also to send us gifts in kind: unused domestic items, bedding, and clothing for our comrades in Lorient and elsewhere.

Do not avoid the collector but take him your donation every month. It will make it all the easier for him to carry out his charitable work.

Comrade staff and workers, all of you who one day in terrible circumstances might need to seek the aid of our organisation, I leave you to choose between the following:

EGOISM – LACK OF FORESIGHT – LONELINESS

or

ORGANIZATION - COMRADESHIP - SOLIDARITY

I appeal to you to choose the second; I hope that you will not fail to do so.

(...) With these words, we ask you to return to your work and to be generous when the collectors pass among you.

In advance, we thank you in the name of the victims.”

Cash raised:

Total sum: 15,546 Francs

Percentage of employees donating: 79 %

Average sum donated per employee: 6.60 Francs

In comparison to 1942:

Total sum: 2,800 Francs

Percentage of employees donating: 38 %

Average sum donated per employee: 1.22 Francs”

“To mark the end of the week, the local Committee organised a meal for the children of prisoners of war and the disaster victims of the workshops, and their mothers. The meal was served in a hall in Le Madrillet placed at our disposal by the Sisters of the Saint-Clément Clinic.”

The Comité National des Cheminots also gave a Christmas party for the children of prisoners and disaster victims. The distribution of the toys to the children of the prisoners was carried out by social workers of the district of Rouen. Approximately 300 children were invited and received wooden toys, made by the apprentices of the school of Jumièges. In addition to the gifts, a show was put on in the community centre by clowns from the Rouen circus.

The evacuation

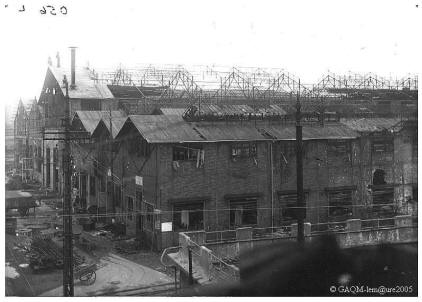

From January to March 1943, with the bombing of Sotteville and its railway infrastructure becoming particularly intense, the SNCF designated the zone as one of very high-risk. The centre of Sotteville had suffered the effects of the many raids which targeted the motive power depot, Sotteville station and the Buddicom works and so it became urgent to avoid further risk to the QM staff by evacuating them to safer localities.

At the beginning of March 1943, 100 blue-collar workers were assigned to various depots in the Paris region, one of which was Batignolles. Their departure coincided with a more direct threat to QM when on March 12th 1943, the Buddicom works was severely damaged with bombs landing right up to the entrance to Quatre-Mares. The disaster of March 28th 1943 served only to accelerate the evacuation. Sizeable groups of workers were formed up, each with their corresponding foreman or supervisor.

360 workers were assigned to the La Lilloise plant at Aulnay-sous-Bois, which could handle major locomotives repairs.

At Batignolles, 160 men set up an accident repair shop.

QM’s instrument workshop together with its 30 workers was transferred to Bois-Colombes where they continued to repair Flaman recorders, Augereau locks and pressure gauges. At the beginning of 1945, it was decided that this workshop would remain at Bois-Colombes.

160 were sent to the workshops at Saintes where locomotive repair was stepped up.

The Vauzelles workshops of the CGCEM in Nevers received 150 men. This establishment was taken over by the SNCF on May 1st 1945.

200 workers were also sent to La Folie workshops at Nanterre and to the depots at Achères, Montrouge, Mantises, Le-Havre, Château-du-Loir, Niort, Rennes, Laval, Auray etc.....

It is not difficult to imagine all the worries and problems for the men sent far from their families. What cannot be overlooked either is the great effort of those involved in these various secondments to make so many locomotives available to the motive power departments from October 1944.

All the same, it is interesting to note that this policy of dispersion of staff and machine tools put an end to QM’s productive capacity well before the Liberation.

The air raids

The modernity and the importance of Sotteville’s railway installations in 1939 explains the interest the town represented for the main players in the conflict, the harsh realities of the Occupation only aggravating those of the war itself.

After the German bombing raids on June 5th and 9th with the arrival of their forces in the area came, with increasing frequency, those the Allies which sought to destabilize the enemy in place.

the main offices

The raids of 1941 and 1942 made the people of Sotteville realise that the real danger came from the sky. They would above all understand that their railway, this essential crossroads of communications which had always been at the very centre of life in the town, was going to become the cause of their fateful destiny.

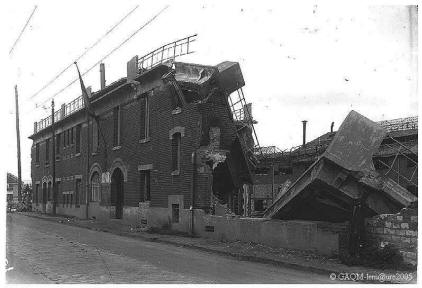

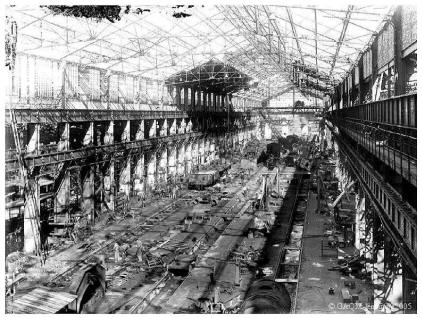

The output capacity of the Quatre-Mares workshops, and their proximity to the station at Sotteville, made them a strategic objective of the greatest importance. They were thus the target of repeated air raids: from 1943 until the Liberation, 153 large calibre bombs fell within the perimeter of the workshops, resulting in their almost total destruction.

"C" hall

The two heaviest raids were those of 28th March 1943 and 19th April 1944. On 28th March, bombs hit the main building. It was a Sunday and the works were practically deserted when at 12.50, the air raid warning sounded. Three minutes later, the bombers released their combined load of nearly 500 medium bombs on Etienne-du-Rouvray and Amfreville from a height of 3,000 metres. At the Quatre-Mares plant, 64 bombs fell around the buildings. Many of them were fitted with delayed action devices which meant that the plant had to be evacuated until they could be defused. The trolley of a 40 tonne overhead travelling crane as well as a 32 tonne crane was demolished. However, under pressure from the German authorities, repairs to the workshops were actively pursued. Unfortunately, just when the work was practically finished, the raid of 19 April 1944, with 81 bombs, ruined a year’s work in just a few moments. In that year of 1944, the horror of the previous years turned into an absolute nightmare.

The main building

Thanks to its importance as a railway town and especially for its proximity to the June 6th 1944 D-Day landing beaches, Sotteville would suffer even more under the Allied “Green Plan” which called for a continuous air attack lasting 90 days on 72 carefully chosen targets, of which 33 were in France. The risks for civilians resulting from the bombing of railway targets posed a real moral dilemma: the likely number of casualties was put at between 8,000 and 16,000.

Nevertheless, even if railway traffic on D-Day was reduced by only ten per cent, the risk had to be taken. General Koenig considered it worthwhile in order to get of the Germans and so on March 27th 1944, the decision was taken, though not without Prime Minister Churchill demanding care from the bomber crews on both humanitarian and political grounds. These last attacks in preparation for the Normandy landings, intended to finish off an enemy already in retreat, ended by leaving a bitter taste to the victory and Liberation of August 31st 1944.

Starting January and up to April 19th 1944, there were 93 air raid warnings but shortly after midnight on April 19th, the allied air forces brought destruction to Sotteville on an apocalyptic scale.

According to “The Times” of April 2Oth, the objective of the allies was to destroy the important marshalling yards which were being used by the German forces.

Flying high above Rouen and its conurbation, the bombers released their loads without any great precision. They used the technique known as “carpet bombing” which consisted of releasing a maximum number of bombs in a minimum time over a specific area. In three successive waves, the planes dropped 6,000 bombs on Rouen, Bonsecours, Amfreville, Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray, Petit-Quevilly and Grand-Quevilly, Bois-Guillaume and Sotteville-lès-Rouen which was the hardest hit with more than 4,625 bomb strikes.

It was five minutes past midnight when the drone of aircraft was heard. Two minutes later, the whole town was lit up by flares and the noise of heavy anti-aircraft fire and exploding bombs could be heard.

It was not until sixteen minutes past midnight that the air raid warning sounded. As a result, the bombs fell on a sleeping population who had no time to get to the shelters. In all, 1,500 tons of bombs were dropped on Sotteville that night.

At the QM workshops, 81 bomb impacts were logged. When the all-clear sounded, those Sottevillais still alive discovered the horror. In only 55 minutes, 200 hectares of the town, out of a total of 700 were laid waste. All the usual emergency services were mobilized; the SNCF rescue teams, the ambulances, the nurses, the fire brigade, the clearance teams and volunteers. But the scale of the disaster was such that Sotteville had to ask for assistance from the Rouen teams.

It was 3.15 in the morning when the hospital trains were made up to evacuate the wounded as quickly as possible. A report by the headquarters of the southern section of the Rouen civil defence refers to the participation of the Rouen rescue teams rapidly reinforced by 24 men from the Le Havre civil defence, the Vernon fire brigade with an ambulance and 20 men, two clearance teams from Les Andelys, a rescue team from Evreux civil defence, about fifty clearance workers from Le Havre, and police cadets as well as 500 young miners. The human tragedy was heart-rending with, on all sides, the most horrifying scenes. In the streets, parts of human bodies could be seen on the roofs and hanging from electric power lines.

“In the street, on each side, the houses had collapsed and the town looked to me like a vast plain dotted with the skeletons of the buildings... It was as if a giant hammer had pulverised the town. There were gaping bomb craters everywhere”. (Mme Rocchia)

The raid took a heavy toll. The municipality’s estimates were as follows:

- 531 dead including 13 railway employees

- 14 missing

- 226 seriously wounded

- 1,575 made homeless

- Approximately one hundred slightly injured

However, it is difficult to give exact figures of the number of casualties. Two years later, corpses were still being found in the rubble.

On May 9th between 6 pm and 8.10 pm, eight bombs fell on Quatre-Mares and the avenue du 14 juillet. It was essential to defuse the delayed action bombs designed to detonate spontaneously at random. This grim task fell mainly to “volunteer” prisoners: they were political detainees of the Rouen law courts who were offered a remission in their sentences for carrying out this work.

In the meantime, no useful activity could be undertaken by the QM staff and all preparatory work for the expedition of machines or parts to the MPDs had to be suspended. The personnel and accounts departments were moved away to the rue du Champs-des-Oiseaux in Rouen and worked there as far as the frequent air raid warnings allowed.

Throughout May, the sirens and anti-aircraft guns were heard daily. The squadrons targeted Sotteville and particularly Rouen during the infamous “Red Week” from May 30th till June 5th 1944. In fact the entire region was under allied fire. On June 12th and 22nd and July 4th, 8th, 15th, 18th and 25th, the MPD and the QM workshops were hit. But this time, it wasn’t the railway installations which were targeted but rather a group of telephone cables running under the rue de Paris. The allies believed that these cables carried German signals from Normandy to Paris.

At the end of July, it could be said that the allies had achieved their objective; the railway at Sotteville was to all intents and purposes reduced to nothing. The locomotives hardly ever left their depots any more. The allies had succeeded in annihilating Sotteville and the whole of the Ouest region.

They had achieved their aim: the Germans were unable to bring up reinforcements during their rout of August. The precipitate departure in June 1944 of the German Director of Control and his staff enabled the workshops to avoid final destruction by the Germans.

The bombing had severely damaged the installations, the buildings, the overhead cranes, and all the services - electric cables, air ducts, steam pipes, oxygen, acetylene, compressed air and hydraulic lines, water and gas pipes. Kilometres of every category had to be replaced. Machine tools and electric motors had been seriously damaged too both by the bombing but also and more especially by the effects of rain and snow.

If on August 31st 1944, the war was far from over, the railway workers, like all Sottevillais, no longer had to fear air from raids or the presence of the Germans. By then, both the enemy and the allies were far away. But the price paid by the railway community in Sotteville was a terrible one:

- 108 railwaymen killed in the air raids

- 30 killed by enemy action

- 17 dead in the camps (out of 21 deportees)

- 4 shot for their political beliefs- more than 300 homes totally destroyed

- nearly 900 homes damaged

translation by John Salter

© GAQM2016 joel.lemaure@outlook.fr

.jpg)

.jpg)